We have now considered the elements of programming: We have used

primitive arithmetic operations, we have combined these operations, and

we have abstracted these composite operations by defining them as compound

functions.

But that is not enough to enable us to say that we know

how to program. Our situation is analogous to that of someone who has

learned the rules for how the pieces move in chess but knows nothing

of typical openings, tactics, or strategy. Like the novice chess

player, we don’t yet know the common patterns of usage in the domain.

We lack the knowledge of which moves are worth making (which

functions

are worth defining). We lack the experience to predict the

consequences of making a move (executing a

function).

The ability to visualize the consequences of the actions under

consideration is crucial to becoming an expert programmer, just as it

is in any synthetic, creative activity. In becoming an expert

photographer, for example, one must learn how to look at a scene and

know how dark each region will appear on a print for each possible

choice of exposure and development conditions. Only then can one

reason backward, planning framing, lighting, exposure, and development

to obtain the desired effects. So it is with programming, where we

are planning the course of action to be taken by a process and where

we control the process by means of a program. To become experts, we

must learn to visualize the processes generated by various types of

functions.

Only after we have developed such a skill can we learn

to reliably construct programs that exhibit the desired behavior.

A function

is a pattern for the local evolution of a

computational process. It specifies how each stage of the process is

built upon the previous stage. We would like to be able to make

statements about the overall, or global, behavior of a

process whose local evolution has been specified by a

function.

This is very difficult to do in general, but we can at least try to

describe some typical patterns of process evolution.

In this section we will examine some common “shapes” for processes

generated by simple

functions.

We will also investigate the

rates at which these processes consume the important computational

resources of time and space.

The

functions

we will consider

are very simple. Their role is like that played by test patterns in

photography: as oversimplified prototypical patterns, rather than

practical examples in their own right.

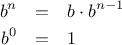

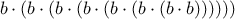

We begin by considering the factorial function, defined by

There are many ways to compute factorials. One way is to make use of

the observation that

is equal to

times

for

any positive integer

:

Thus, we can compute

by computing

and multiplying the

result by

. If we add the stipulation that 1!

is equal to 1,

this observation translates directly into a

function:

function factorial(n) {

if (n === 1)

return 1;

else return n * factorial(n-1);

}

|

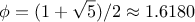

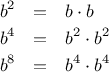

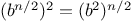

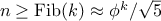

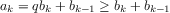

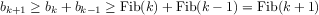

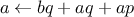

Figure 1.

3 A linear recursive process for computing 6!.

|

Instead of a conditional statement, we can use a conditional expression

in the body of the function, which leads to this definition of the

factorial function:

function factorial(n) {

return n === 1 ? 1 : n * factorial(n-1);

}

In this version, the body of the function consists of only a

return

statement, and thus we can use the substitution model of

section

1.1.5 to watch the

function in action

computing 6!, as shown in figure

1.3.

Now let’s take a different perspective on computing factorials. We

could describe a rule for computing

by

specifying that we

first multiply 1 by 2, then multiply the result by 3, then by 4,

and so on until we reach

.

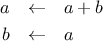

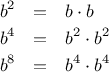

More formally, we maintain a running product, together with a counter

that counts from 1 up to

. We can describe the computation by

saying that the counter and the product simultaneously change from one

step to the next according to the rule

product  counter

counter  product

product

counter  counter

counter  1

1

and stipulating that

is the value of the product when

the counter exceeds

.

Once again, we can recast our description as a

function

for computing

factorials:

1

function factorial(n) {

return fact_iter(1,1,n);

}

function fact_iter(product,counter,max_count) {

if (counter > max_count)

return product;

else return fact_iter(counter*product,

counter+1,

max_count);

}

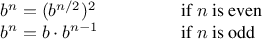

|

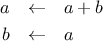

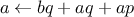

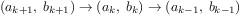

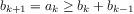

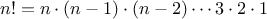

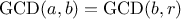

Figure 1.

4 A linear iterative process for computing

.

|

As before, we can define an alternative version whose body only consists of

a

return statement.

function factorial(n) {

return fact_iter(1,1,n);

}

function fact_iter(product,counter,max_count) {

return counter > max_count

? product

: fact_iter(counter*product,

counter+1,

max_count);

}

Figure

1.4

visualizes the application of the substitution model

for computing

.

Compare the two processes. From one point of view, they seem hardly

different at all. Both compute the same mathematical function on the

same domain, and each requires a number of steps proportional to

to compute

. Indeed, both processes even carry out the same

sequence of multiplications, obtaining the same sequence of partial

products. On the other hand, when we consider the

“shapes” of the

two processes, we find that they evolve quite differently.

Consider the first process. The substitution model reveals a shape of

expansion followed by contraction, indicated by the arrow in

figure

1.3. The expansion occurs as the

process builds up a chain of

deferred operations (in this case,

a chain of multiplications). The contraction occurs as

the operations are

actually performed. This type of process, characterized by a chain of

deferred operations, is called a

recursive process. Carrying

out this process requires that the interpreter keep track of the

operations to be performed later on. In the computation of

,

the length of the chain of deferred multiplications, and hence the amount

of information needed to keep track of it,

grows linearly with

(is proportional to

), just like the number of steps.

Such a process is called a

linear recursive process.

By contrast, the second process does not grow and shrink. At each

step, all we need to keep track of, for any

, are the current

values of the variables

product,

counter, and

max_count. We call this an

iterative process. In general, an

iterative process is one whose state can be summarized by a fixed

number of

state variables, together with a fixed rule that

describes how the state variables should be updated as the process

moves from state to state and an (optional) end test that specifies

conditions under which the process should terminate. In computing

, the number of steps required grows linearly with

. Such a process is

called a

linear iterative process.

The contrast between the two processes can be seen in another way. In

the iterative case, the program variables provide a complete

description of the state of the process at any point. If we stopped

the computation between steps, all we would need to do to resume the

computation is to supply the interpreter with the values of the three

program variables. Not so with the recursive process. In this case

there is some additional “hidden” information, maintained by the

interpreter and not contained in the program variables, which

indicates “where the process is” in negotiating the chain of

deferred operations. The longer the chain, the more information must

be maintained.

2

In contrasting iteration and recursion, we must be careful not to

confuse the notion of a

recursive process with the notion of a

recursive

function.

When we describe a function as recursive,

we are referring to the syntactic fact that the function definition

refers (either directly or indirectly) to the function itself. But

when we describe a process as following a pattern that is, say,

linearly recursive, we are speaking about how the process evolves, not

about the syntax of how a function is written. It may seem

disturbing that we refer to a recursive function such as

fact_iter

as generating an iterative process. However, the process

really is iterative: Its state is captured completely by its three

state variables, and an interpreter need keep track of only three

variables in order to execute the process.

One reason that the distinction between process and function

may be

confusing is that most programming languages—including

JavaScript—are designed in such a way that the

interpretation of any recursive function consumes an amount of memory

that grows with the number of function calls, even when the process

described is, in principle, iterative. As a consequence, they

can describe iterative processes only by resorting to

special-purpose

“looping constructs” such as

while and

for, which we will encounter

in chapter 3. The language Scheme

does not share this defect. It will

execute an iterative process in constant space, even if the iterative

process is described by a recursive function. An implementation with

this property is called

tail-recursive. With a tail-recursive

implementation,

iteration can be expressed using the ordinary

function call mechanism, so that special iteration constructs are

useful only as

syntactic sugar.

4

Chapter 5 describes a tail-recursive implementation of a subset of JavaScript.

Exercise 1.9.

Each of the following two functions defines a method for adding two

positive integers in terms of the functions

inc,

which increments its argument by 1, and

dec, which decrements

its argument by 1.

function plus(a,b) {

return a === 0 ? b : inc(plus(dec(a),b));

}

function plus(a,b) {

return a === 0 ? b : plus(dec(a),inc(b));

}

Using the substitution model, illustrate the process generated by each

function in evaluating

plus(4,5);. Are these processes iterative or recursive?

Exercise 1.10.

The following function computes a mathematical function called

Ackermann’s function.

function A(x,y) {

if (y === 0)

return 0;

else if (x === 0)

return 2 * y;

else if (y === 1)

return 2;

else return A(x - 1, A(x, y - 1));

}

What are the values of the following expressions?

A(1,10);

A(2,4);

A(3,3);

Consider the following functions, where

A is the function

defined above:

function f(n) {

return A(0,n);

}

function g(n) {

return A(1,n);

}

function h(n) {

return A(2,n);

}

function k(n) {

return 5 * n * n;

}

Give concise mathematical definitions for the functions computed by

the functions

f,

g, and

h for positive integer

values of

. For example,

(k n) computes

.

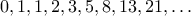

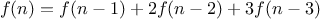

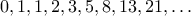

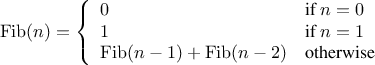

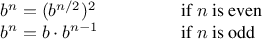

Another common pattern of computation is called

tree recursion.

As an example, consider computing the sequence of

Fibonacci numbers,

in which each number is the sum of the preceding two:

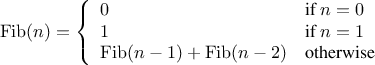

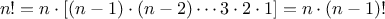

In general, the Fibonacci numbers can be defined by the rule

We can immediately translate this definition into a recursive

function for computing Fibonacci numbers:

function fib(n) {

if (n === 0)

return 0;

else if (n === 1)

return 1;

else return fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2);

}

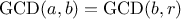

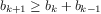

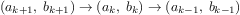

|

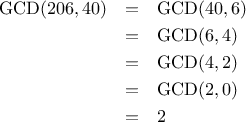

Figure 1.

5 The tree-recursive process generated in computing

fib(5).

|

Consider the pattern of this computation. To compute

fib(5),

we compute

fib(4)

and

fib(3).

To compute

fib(4),

we compute

fib(3)

and

fib(2). In general, the evolved

process looks like a tree, as shown in figure

1.5.

Notice that the branches split into two at each level (except at the

bottom); this reflects the fact that the

fib

function

calls itself twice each time it is invoked.

This

function

is instructive as a prototypical tree recursion, but it

is a terrible way to compute Fibonacci numbers because it does so much

redundant computation. Notice in figure

1.5 that

the entire computation of

(fib 3)—almost half the work—is

duplicated. In fact, it is not hard to show that the number of times

the function will compute

(fib 1) or

(fib 0) (the number

of leaves in the above tree, in general) is precisely

. To get an idea of how bad this is, one can show that the

value of

grows exponentially with

. More precisely

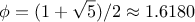

(see exercise

1.13),

is the closest

integer to

, where

is the

golden ratio, which satisfies the equation

Thus, the process uses a number of steps that grows exponentially

with the input. On the other hand, the space required grows only

linearly with the input, because we need keep track only of which

nodes are above us in the tree at any point in the computation. In

general, the number of steps required by a tree-recursive process will be

proportional to the number of nodes in the tree, while the space

required will be proportional to the maximum depth of the tree.

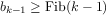

We can also formulate an iterative process for computing the

Fibonacci numbers. The idea is to use a pair of integers

and

,

initialized to

and

,

and to repeatedly apply the simultaneous

transformations

It is not hard to show that, after applying this transformation

times,

and

will be equal, respectively, to

and

. Thus, we can compute Fibonacci numbers iteratively using

the function

function fib(n) {

return fib_iter(1,0,n);

}

function fib_iter(a,b,count) {

if (count === 0)

return b;

else return fib_iter(a + b,a,count - 1);

}

This second method for computing

is a linear iteration. The

difference in number of steps required by the two methods—one linear in

,

one growing as fast as

itself—is enormous, even for

small inputs.

One should not conclude from this that tree-recursive processes are

useless. When we consider processes that operate on hierarchically

structured data rather than numbers, we will find that tree recursion

is a natural and powerful tool.

5 But even in numerical operations,

tree-recursive processes can be useful in helping us to understand and

design programs. For instance, although the first

fib

function

is much less efficient than the second one, it is more

straightforward, being little more than a translation into

JavaScript

of the

definition of the Fibonacci sequence. To formulate the iterative

algorithm required noticing that the computation could be recast as an

iteration with three state variables.

Example: Counting change

It takes only a bit of cleverness to come up with the iterative

Fibonacci algorithm. In contrast, consider the

following problem: How many different ways can we make change of

,

given half-dollars, quarters, dimes, nickels, and pennies? More

generally, can we write a

function

to compute the number of ways to change any given amount of money?

To see why this is true, observe that the ways to make change can be

divided into two groups: those that do not use any of the first kind

of coin, and those that do. Therefore, the total number of ways to

make change for some amount is equal to the number of ways to make

change for the amount without using any of the first kind of coin,

plus the number of ways to make change assuming that we do use the

first kind of coin. But the latter number is equal to the number of

ways to make change for the amount that remains after using a coin of

the first kind.

We can easily translate this description into a recursive

function:

function count_change(amount) {

return cc(amount,5);

}

function cc(amount,kinds_of_coins) {

if (amount === 0)

return 1;

else if (amount < 0 ||

kinds_of_coins === 0)

return 0;

else return cc(amount,kinds_of_coins - 1)

+

cc(amount - first_denomination(

kinds_of_coins),

kinds_of_coins);

}

function first_denomination(kinds_of_coins) {

switch(kinds_of_coins) {

case 1: return 1;

case 2: return 5;

case 3: return 10;

case 4: return 25;

case 5: return 50;

}

}

(The

first_denomination

function

takes as input the number of

kinds of coins available and returns the denomination of the first

kind. Here we are thinking of the coins as arranged in order from

largest to smallest, but any order would do as well.) We can now

answer our original question about changing a dollar:

count_change(100);

The function

count_change

generates a tree-recursive process with

redundancies similar to those in our first implementation of

fib.

(It will take quite a while for that 292 to be computed.) On

the other hand, it is not obvious how to design a better algorithm

for computing the result, and we leave this problem as a challenge.

The observation that a

tree-recursive process may be highly

inefficient but often easy to specify and understand has led people to

propose that one could get the best of both worlds by designing a

“smart compiler” that could transform tree-recursive

functions

into more efficient

functions

that compute the same result.

7

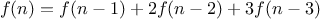

Exercise 1.11.

A function

is defined by the rule that

if

and

if

. Write a JavaScript function that

computes

by means of a recursive process. Write a function that

computes

by means of an iterative process.

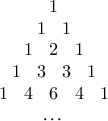

Exercise 1.12.

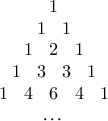

The following pattern of numbers is called

Pascal’s triangle.

The numbers at the edge of the triangle are all 1, and

each number inside the triangle is the sum of the two numbers

above it.

8

Write a function that computes elements of Pascal’s triangle by means

of a recursive process.

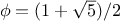

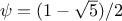

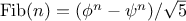

Exercise 1.13.

Prove that

is the closest integer to

,

where

. Hint: Let

. Use

induction and the definition of the Fibonacci numbers (see

section

1.2.2) to prove that

.

The previous examples illustrate that processes can differ

considerably in the rates at which they consume computational

resources. One convenient way to describe this difference is to use

the notion of

order of growth to obtain a gross measure of the

resources required by a process as the inputs become larger.

Let

be a parameter that measures the size of the problem,

and let

(

) be the amount

of resources the process requires for a problem

of size

. In our previous examples we took

to be the number

for which a given function is to be computed, but there are other

possibilities. For instance, if our goal is to compute an

approximation to the square root of a number, we might take

to be

the number of digits accuracy required. For matrix multiplication we

might take

to be the number of rows in the matrices.

In general there are a number of properties of the problem with respect to which

it will be desirable to analyze a given process.

Similarly,

(

)

might measure the number of internal storage registers used, the

number of elementary machine operations performed, and so on. In

computers that do only a fixed number of operations at a time, the

time required will be proportional to the number of elementary machine

operations performed.

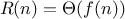

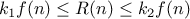

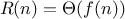

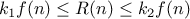

We say that

has order of growth

, written

(pronounced “theta of

”), if there are

positive constants

and

independent of

such that

for any sufficiently large value of

. (In other

words, for large

,

the value

is sandwiched between

and

.)

For instance, with the linear recursive process for computing

factorial described in section

1.2.1 the

number of steps grows proportionally to the input

. Thus, the

steps required for this process grows as

. We also saw

that the space required grows as

.

For the

iterative

factorial function, the number of steps is still

.

A properly tail-recursive implementation of Scheme will require space of

—that is,

constant space—whereas JavaScript's space requirement for the iterative factorial function

is still

.

10

The

tree-recursive Fibonacci computation requires

steps and space

, where

is the

golden ratio described in section

1.2.2.

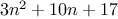

Orders of growth provide only a crude description of the behavior of a

process. For example, a process requiring

steps and a process

requiring

steps and a process requiring

steps

all have

order of growth. On the other hand, order of

growth provides a useful indication of how we may expect the behavior

of the process to change as we change the size of the problem. For a

(linear) process, doubling the size will roughly double the amount

of resources used. For an

exponential process, each increment in

problem size will multiply the resource utilization by a constant

factor. In the remainder of section

1.2

we will examine two

algorithms whose order of growth is

logarithmic, so that doubling the

problem size increases the resource requirement by a constant amount.

Exercise 1.14.

Draw the tree illustrating the process generated by the

count_change

function

of section

1.2.2 in making

change for 11 cents. What are the orders of growth of the space and

number of steps used by this process as the amount to be changed

increases?

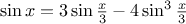

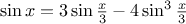

Exercise 1.15.

The sine of an angle (specified in

radians) can be computed by making use of the approximation

if

is

sufficiently small, and the trigonometric identity

to reduce the size of the argument of

. (For

purposes of this exercise an angle is considered “sufficiently

small” if its magnitude is not greater than 0.1 radians.) These

ideas are incorporated in the following

functions:

function cube(x) {

return x * x * x;

}

function p(x) {

return 3 * x - 4 * cube(x);

}

function sine(angle) {

if (! (abs(angle) > 0.1))

return angle;

else return p(sine(angle / 3.0));

}

- How many times is the function p

applied when (sine 12.15) is evaluated?

-

What is the order of growth in space and number of steps (as a

function of

) used by the process generated by the sine

function when (sine a) is evaluated?

) used by the process generated by the sine

function when (sine a) is evaluated?

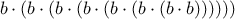

Consider the problem of computing the exponential of a given number.

We would like a function that takes as arguments a base

and a

positive integer exponent

and computes

. One way to do this

is via the recursive definition

which translates readily into the function

function expt(b,n) {

if (n === 0)

return 1;

else return b * expt(b, n - 1);

}

This is a linear recursive process, which requires

steps

and

space. Just as with factorial, we can readily

formulate an equivalent linear iteration:

function expt(b,n) {

return expt_iter(b,n,1);

}

function expt_iter(b,counter,product) {

if (counter === 0)

return product;

else return expt_iter(b,

counter - 1,

b * product);

}

This version requires

steps and

space.

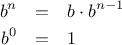

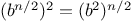

We can compute exponentials in fewer steps by using successive

squaring. For instance, rather than computing

as

we can compute it using three multiplications:

This method works fine for exponents that are powers of 2. We can

also take advantage of successive squaring in computing exponentials

in general if we use the rule

We can express this method as a function:

function fast_expt(b,n) {

if (n === 0)

return 1;

else if (is_even(n))

return square(fast_expt(b, n / 2));

else return b * fast_expt(b, n - 1);

}

function is_even(n) {

return n % 2 === 0;

}

where the predicate to test whether an integer is even is defined in terms of

the

operator

%, which computes the remainder after integer division, by

function is_even(n) {

return n % 2 === 0;

}

The process evolved by

fast_expt

grows logarithmically with

in both space and number of steps. To see this, observe that

computing

using

fast_expt

requires only one more

multiplication than computing

. The size of the exponent we can

compute therefore doubles (approximately) with every new

multiplication we are allowed. Thus, the number of multiplications

required for an exponent of

grows about as fast as the logarithm

of

to the base 2. The process has

growth.

11

The difference between

growth and

growth

becomes striking as

becomes large. For example,

fast_expt

for

requires only 14

multiplications.

12

It is also possible to use the idea of

successive squaring to devise an iterative algorithm that computes

exponentials with a logarithmic number of steps

(see exercise

1.16), although, as is often

the case with iterative algorithms, this is not written down so

straightforwardly as the recursive algorithm.

13

Exercise 1.16.

Design a function that evolves an iterative exponentiation process

that uses successive squaring and uses a logarithmic number of steps,

as does

fast_expt.

(Hint: Using the observation that

, keep, along with the exponent

and the

base

, an additional state variable

, and define the state

transformation in such a way that the product

is unchanged

from state to state. At the beginning of the process

is taken to

be 1, and the answer is given by the value of

at the end of the

process. In general, the technique of defining an

invariant

quantity that remains unchanged from state to state is a powerful way

to think about the

design of iterative algorithms.)

Exercise 1.17.

The exponentiation algorithms in this section are based on performing

exponentiation by means of repeated multiplication. In a similar way,

one can perform integer multiplication by means of repeated addition.

The following multiplication function (in which it is assumed that

our language can only add, not multiply) is analogous to the

expt function:

function times(a,b) {

if (b === 0)

return 0;

else return a + a * (b - 1);

}

This algorithm takes a number of steps that is linear in

b.

Now suppose we include, together with addition, operations

double,

which doubles an integer, and

halve, which divides an (even)

integer by 2. Using these, design a multiplication function analogous

to

fast_expt

that uses a logarithmic number of steps.

Exercise 1.18.

Using the results of exercises

1.16

and

1.17, devise a function that generates an iterative

process for multiplying two integers in terms of adding, doubling, and

halving and uses a logarithmic number of steps.

14

Exercise 1.19.

There is a clever algorithm for computing the Fibonacci numbers in

a logarithmic number of steps.

Recall the transformation of the state variables

and

in the

fib_iter

process of

section

1.2.2:

and

. Call this transformation

, and observe that applying

over

and over again

times, starting with 1 and 0, produces the pair

and

. In other words, the Fibonacci

numbers are produced by applying

, the

th power of the

transformation

, starting with the pair

. Now consider

to be the special case of

and

in a family of

transformations

, where

transforms the pair

according to

and

. Show

that if we apply such a transformation

twice, the effect is

the same as using a single transformation

of the same form,

and compute

and

in terms of

and

. This gives us an

explicit way to square these transformations, and thus we can compute

using successive squaring, as in the

fast_expt

function. Put this all together to complete the following function,

which runs in a logarithmic number of

steps:

15

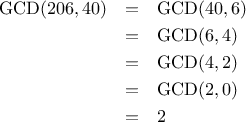

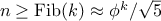

The greatest common divisor (GCD) of two integers

and

is

defined to be the largest integer that divides both

and

with no remainder.

For example, the GCD of 16 and 28 is 4. In chapter 2,

when we investigate how to implement rational-number arithmetic, we

will need to be able to compute GCDs in order to reduce

rational numbers to lowest terms. (To reduce a rational number to

lowest terms, we must divide both the numerator and the denominator by their

GCD. For example, 16/28 reduces to 4/7.) One way to find the

GCD of two integers is to factor them and search for common

factors, but there is a famous algorithm that is much more efficient.

The idea of the algorithm is based on the observation that,

if

is

the remainder when

is divided by

, then the common divisors of

and

are

precisely the same as the common divisors of

and

. Thus, we can use the equation

to successively reduce the problem of computing a GCD to the

problem of computing the GCD of smaller and smaller pairs of

integers. For example,

reduces GCD(206,40) to GCD(2,0), which is 2. It is

possible to show that starting with any two positive integers and

performing repeated reductions will always eventually produce a pair

where the second number is 0. Then the GCD is the other

number in the pair. This method for computing the GCD is

known as

Euclid’s Algorithm.

16

It is easy to express Euclid’s Algorithm as a

function:

function gcd(a,b) {

return b === 0 ? a : gcd(b, a % b);

}

This generates an iterative process, whose number of steps grows as

the logarithm of the numbers involved.

Exercise 1.20.

For a change, we are using a conditional

expression in the

gcd function. Write a

version of

gcd that uses a conditional

statement instead!

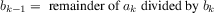

The fact that the number of steps required by Euclid’s Algorithm has

logarithmic growth bears an interesting relation to the Fibonacci

numbers:

Lamé’s Theorem: If Euclid’s Algorithm requires

steps to

compute the GCD of some pair, then the smaller number in the pair

must be greater than or equal to the

steps to

compute the GCD of some pair, then the smaller number in the pair

must be greater than or equal to the  th Fibonacci

number.17

th Fibonacci

number.17

We can use this theorem to get an order-of-growth estimate for Euclid’s

Algorithm. Let

be the smaller of the two inputs to the

function.

If the process takes

steps, then we must have

. Therefore

the number of steps

grows as the logarithm (to the base

) of

.

Hence, the order of growth is

.

Exercise 1.21.

The process that a

function

generates is of course dependent on the

rules used by the interpreter. As an example, consider the iterative

gcd

function

given above.

Suppose we were to interpret this

function

using normal-order

evaluation, as discussed in section

1.1.5.

(The normal-order-evaluation rule for

if is described in

exercise

1.5.)

Using the

substitution method (for normal order), illustrate the process

generated in evaluating

gcd(206,40)

and indicate the

remainder operations that are actually performed.

How many

remainder operations are actually performed

in the normal-order evaluation of

gcd(206,40)?

In the applicative-order evaluation?

This section describes two methods for checking the primality of an

integer

, one with order of growth

, and a

“probabilistic” algorithm with order of growth

. The

exercises at the end of this section suggest programming

projects based on these algorithms.

Searching for divisors

Since ancient times, mathematicians have been fascinated by problems

concerning prime numbers, and many people have worked on the problem

of determining ways to test if numbers are prime. One way

to test if a number is prime is to find the number’s divisors. The

following program finds the smallest integral divisor (greater than 1)

of a given number

. It does this in a straightforward way, by

testing

for divisibility by successive integers starting with 2.

function smallest_divisor(n) {

return find_divisor(n,2);

}

function find_divisor(n,test_divisor) {

if (square(test_divisor) > n)

return n;

else if (divides(test_divisor,n))

return test_divisor;

else return find_divisor(n, test_divisor + 1);

}

function divides(a,b) {

return b % a === 0;

}

We can test whether a number is prime as follows:

is prime if

and only if

is its own smallest divisor.

function is_prime(n) {

return n === smallest_divisor(n);

}

The end test for

find_divisor

is based on the fact that if

is not prime it must have a divisor less than or equal to

.

18

This means that the algorithm need only test divisors between 1 and

. Consequently, the number of steps required to identify

as prime will have order of growth

.

The Fermat test

If

is not prime, then, in general, most of the numbers

will not

satisfy the above relation. This leads to the following algorithm for

testing primality: Given a number

, pick a

random number

and

compute the remainder of

modulo

. If the result is not equal to

, then

is certainly not prime. If it is

, then chances are good

that

is prime. Now pick another random number

and test it with the

same method. If it also satisfies the equation, then we can be even more

confident that

is prime. By trying more and more values of

, we can

increase our confidence in the result. This algorithm is known as the

Fermat test.

To implement the Fermat test, we need a function that computes the

exponential of a number modulo another number:

function expmod(base,exp,m) {

if (exp === 0)

return 1;

else if (is_even(exp))

return square(expmod(base,exp/2,m)) % m;

else return (base * expmod(base,exp - 1,m)) % m;

}

This is very similar to the

fast_expt

function of

section

1.2.4. It uses successive squaring, so

that the number of steps grows logarithmically with the

exponent.

20

The Fermat test is performed by choosing at random a number

between 1 and

inclusive and checking whether the remainder

modulo

of the

th power of

is equal to

. The random

number

is chosen using the function

random, which we assume is

included as a primitive in Scheme.

The function

random

returns a

nonnegative integer less than its integer input. Hence, to obtain a random

number between 1 and

,

we call

random with an input of

and add 1 to the result:

function fermat_test(n) {

function try_it(a) {

return expmod(a,n,n) === a;

}

return try_it(1 + random(n - 1));

}

The following

function

runs the test a given number of times, as

specified by a parameter. Its value is true if the test succeeds

every time, and false otherwise.

function fermat_test(n) {

function try_it(a) {

return expmod(a,n,n) === a;

}

return try_it(1 + random(n - 1));

}

function fast_is_prime(n,times) {

if (times === 0)

return true;

else if (fermat_test(n))

return fast_is_prime(n, times - 1);

else return false;

}

Probabilistic methods

The Fermat test differs in character from most familiar algorithms, in

which one computes an answer that is guaranteed to be correct. Here,

the answer obtained is only probably correct. More precisely, if

ever fails the Fermat test, we can be certain that

is not prime.

But the fact that

passes the test, while an extremely strong

indication, is still not a guarantee that

is prime. What we would

like to say is that for any number

, if we perform the test enough

times and find that

always passes the test, then the probability

of error in our primality test can be made as small as we like.

Unfortunately, this assertion is not quite correct. There do exist

numbers that fool the Fermat test: numbers

that are not prime and

yet have the property that

is congruent to

modulo

for

all integers

. Such numbers are extremely rare, so the Fermat

test is quite reliable in practice.

21

There are variations of the Fermat test that cannot be fooled. In

these tests, as with the Fermat method, one tests the primality of an

integer

by choosing a random integer

and checking some

condition that depends upon

and

. (See

exercise

1.29 for an example of such a test.) On the

other hand, in contrast to the Fermat test, one can prove that, for

any

, the condition does not hold for most of the integers

unless

is prime. Thus, if

passes the test for some random

choice of

, the chances are better than even that

is prime. If

passes the test for two random choices of

, the chances are better

than 3 out of 4 that

is prime. By running the test with more and

more randomly chosen values of

we can make the probability of

error as small as we like.

The existence of tests for which one can prove that the chance of

error becomes arbitrarily small has sparked interest in algorithms of

this type, which have come to be known as

probabilistic

algorithms. There is a great deal of research activity in this area,

and probabilistic algorithms have been fruitfully applied to many

fields.

22

Exercise 1.22.

Use the

smallest_divisor

function

to find the smallest divisor

of each of the following numbers: 199, 1999, 19999.

Exercise 1.23.

Assume that our JavaScript interpreter defines a primitive called

runtime

that returns an integer that specifies the amount of time the system

has been running (measured, for example, in microseconds). The

following

timed_prime_test

function,

when called with an

integer

, prints

and

checks to see if

is prime.

If

is

prime, the

function

prints three asterisks followed by the amount of time

used in performing the test.

function timed_prime_test(n) {

newline();

display(n);

start_prime_test(n,runtime());

}

function start_prime_test(n,start_time) {

if (is_prime(n))

return report_prime(runtime() - start_time);

}

function report_prime(elapsed_time) {

print(" *** ");

display(elapsed_time);

}

Using this

function,

write a

function

search_for_primes

that checks the primality of consecutive odd integers in a specified range.

Use your

function

to find the three smallest primes larger than 1000;

larger than 10,000; larger than 100,000; larger than 1,000,000. Note

the time needed to test each prime. Since the testing algorithm has

order of growth of

,

you should expect that testing

for primes around 10,000 should take about

times as long

as testing for primes around 1000. Do your timing data bear this out?

How well do the data for 100,000 and 1,000,000 support the

prediction? Is your result compatible with the notion that programs

on your machine run in time proportional to the number of steps

required for the computation?

Exercise 1.24.

The

smallest_divisor

function

shown at the start of this section

does lots of needless testing: After it checks to see if the

number is divisible by 2 there is no point in checking to see if

it is divisible by any larger even numbers. This suggests that the

values used for

test_divisor

should not be 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, …

but rather 2, 3, 5, 7, 9, ….

To implement this

change, define a

function

next that returns 3 if its input is

equal to 2 and otherwise returns its input plus 2.

Modify the

smallest_divisor

function

to use

next(test_divisor)

instead of

test_divisor + 1.

With

timed_prime_test

incorporating this modified version of

smallest_divisor,

run the

test for each of the 12 primes found in

exercise

1.23.

Since this modification halves the

number of test steps, you should expect it to run about twice as fast.

Is this expectation confirmed? If not, what is the observed ratio of

the speeds of the two algorithms, and how do you explain the fact that

it is different from 2?

Exercise 1.25.

Modify the

timed_prime_test

function

of exercise

1.23 to use

fast_is_prime

(the Fermat method), and test each of the 12 primes you found in that

exercise. Since the Fermat test has

growth, how would you expect the time to test primes near 1,000,000 to compare

with the time needed to test primes near 1000? Do your data bear this

out? Can you explain any discrepancy you find?

Exercise 1.26.

Alyssa P. Hacker complains that we went to a lot of extra work in

writing

expmod.

After all, she says, since we already know how

to compute exponentials, we could have simply written

function expmod(base,exp,m) {

return fast_expt(base,exp) % m;

}

Is she correct?

Would this

function

serve as well for our fast prime tester? Explain.

Exercise 1.27.

Louis Reasoner is having great difficulty doing

exercise

1.25.

His

fast_is_prime

test seems to run more slowly than his

is_prime

test.

Louis calls his friend Eva Lu Ator over to help. When they examine Louis’s code, they

find that he has rewritten the

expmod

function

to use an

explicit multiplication, rather than calling

square:

function expmod(base,exp,m) {

if (exp === 0)

return 1;

else if (is_even(exp))

return expmod(base,exp/2,m)

* expmod(base,exp/2,m)

% m;

else return base

* expmod(base,exp - 1,m)

% m;

}

“I don’t see what difference that could make,” says Louis.

“I do.” says Eva.

“By writing the

function

like that, you have

transformed the

process into a

process.”

Explain.

Exercise 1.28.

Demonstrate that the Carmichael numbers listed in

footnote

21 of Section 1.2 really do fool

the Fermat test. That is, write a

function

that takes an integer

and tests whether

is congruent to

modulo

for every

, and try your

function

on the given Carmichael numbers.

Exercise 1.29.

One variant of the Fermat test that cannot be fooled is called the

Miller-Rabin test (Miller 1976;

Rabin 1980). This starts from

an alternate form of Fermat’s Little Theorem, which states that if

is a prime number and

is any positive integer less

than

, then

raised to the

st

power is congruent to 1 modulo

. To test

the primality of a number

by the Miller-Rabin test,

we pick a random number

and raise

to the

st power

modulo

using the

expmod

function.

However, whenever we perform the

squaring step in

expmod, we check to see if we have

discovered a

“nontrivial square root of 1

modulo

,

”

that is, a number not

equal to 1 or

whose square is equal to 1

modulo

. It is

possible to prove that if such a nontrivial square root of 1 exists,

then

is not prime.

It is also possible to prove that if

is an

odd number that is not prime, then, for at least half the numbers

, computing

in this way will reveal a nontrivial

square root of 1 modulo

.

(This is why the Miller-Rabin test

cannot be fooled.) Modify the

expmod

function

to signal if it

discovers a nontrivial square root of 1, and use this to implement

the Miller-Rabin test with a

function

analogous to

fermat_test.

Check your

function

by testing various known primes and non-primes.

Hint: One convenient way to make

expmod

signal is to have it return 0.

is equal to

is equal to

times

times  for

any positive integer

for

any positive integer  :

:

by computing

by computing

and multiplying the

result by

and multiplying the

result by  . If we add the stipulation that 1!

is equal to 1,

this observation translates directly into a

function:

. If we add the stipulation that 1!

is equal to 1,

this observation translates directly into a

function: